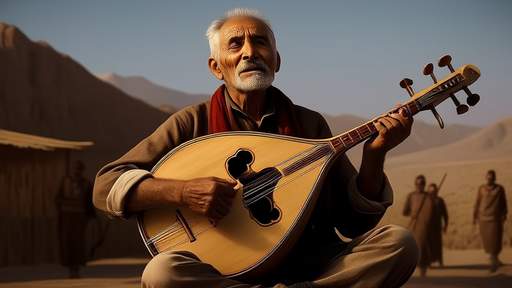

The rebab, a delicate bowed string instrument with a pear-shaped body, resonates through the centuries as a living testament to Islam's cultural journey across the Malay Archipelago. Unlike the metallic clang of gamelan or the rhythmic pulse of drums, its mournful, human-like voice carries whispers of distant deserts and Sufi mystics who sailed monsoon winds to Southeast Asia. This unassuming instrument, often overshadowed by more flamboyant traditional counterparts, holds within its horsehair strings an untold story of religious transformation, artistic synthesis, and the quiet persistence of spiritual expression.

Historical accounts suggest the rebab arrived in Malaysia between the 13th-15th centuries, carried by Arab and Persian traders along the maritime Silk Road. What makes its adoption remarkable is how seamlessly it became woven into indigenous performance traditions while simultaneously serving as an auditory symbol of Islamic identity. In the royal courts of Malacca, the rebab's microtonal melodies accompanied the recitation of Hikayat epics - stories of Islamic prophets adapted into Malay verse. Its presence transformed these performances from mere entertainment into acts of devotion, the bow's movement across strings mirroring the rhythmic cadence of Quranic recitation.

The instrument's physical form reveals layers of cultural negotiation. Early Malaysian rebabs show distinct modifications from their Middle Eastern ancestors - the wooden body often incorporates native tropical hardwoods, while the bow adopts a more pronounced curve to accommodate playing techniques borrowed from local fiddle traditions. This hybridization speaks volumes about how Islam took root in the region: not through cultural erasure, but through creative adaptation. The rebab became a bridge between worlds, its sound neither wholly foreign nor entirely local, much like the brand of Islam that flourished in the Nusantara.

Scholars have noted the rebab's unique role in Sufi conversion strategies. Unlike the bedug drum whose loud calls signaled prayer times, the rebab operated in intimate spaces. Sufi mystics would play meditative improvisations (taqsim) during nighttime gatherings, the instrument's haunting tones inducing trance-like states that opened participants to spiritual revelation. This subtle approach to devotion resonated deeply with Malay animist traditions that valued inner mystical experience, making the rebab an unlikely but effective missionary tool. Even today, certain rural wayang kulit performances retain traces of this practice, where the rebab player's improvisations between scenes serve as aural reminders of divine presence.

Modern challenges threaten the rebab's continuity. The rise of electronic Islamic pop music and conservative attitudes labeling certain instruments as "un-Islamic" have pushed this cultural artifact to the margins. Yet in pockets of tradition - like the Mak Yong theater of Kelantan or the Zapin dance accompaniments of Johor - the rebab's voice endures. Contemporary craftsmen like Pak Ahmad of Terengganu still hand-carve rebabs using century-old techniques, while young ethnomusicologists document fading playing styles before they disappear entirely. Their efforts ensure that this bowed witness to Malaysia's Islamic journey continues to sing its story to generations yet unborn.

What makes the rebab's tale compelling isn't just its historical significance, but its metaphorical richness. Like Islam in Malaysia, it adapted without losing its essence, found harmony without sacrificing identity, and created beauty through cultural conversation rather than conquest. In an age of religious polarization, the rebab stands as a reminder that faith often travels not through dogma alone, but through shared artistic expression that speaks directly to the human soul. Its strings, when bowed with skill and reverence, still produce sounds that transcend time - a musical salam from the past to the present, and perhaps, to the future.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025