The olive tree has long stood as a silent witness to the unfolding history of Palestine. Its gnarled trunks and silver-green leaves have shaded generations, its roots digging deep into a land marked by both abundance and strife. But in recent years, a new sound has emerged from these ancient trees—not the rustle of leaves or the creak of branches, but something far more haunting: the olive wood’s whispered lament, a sound that seems to carry the weight of centuries.

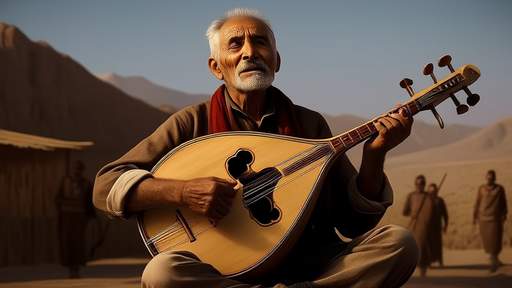

Across the West Bank and Gaza, artisans and musicians have begun crafting flutes and wind instruments from olive wood, a material once reserved for carvings and prayer beads. The resulting music is unlike anything produced by conventional instruments. It is raw, breathy, and suffused with an almost human sorrow—a sound that locals describe as "the land itself crying out." Some say it mirrors the collective grief of a people who have endured decades of displacement and conflict. Others hear in it the resilience of a culture that refuses to be silenced.

The phenomenon has drawn attention beyond Palestine’s borders. Ethnomusicologists from Europe and North America have traveled to villages like Beit Sahour and Jenin to record these instruments, analyzing their unique acoustic properties. What they’ve found is striking: the density and age of olive wood, shaped by years of drought and hardship, create vibrations that conventional spruce or maple cannot replicate. The older the tree, the more textured and layered the sound—each note carrying echoes of the past.

Yet this musical revival is not without controversy. Some Palestinian elders view the trend as a distortion of tradition, arguing that olive wood should remain sacred, untouched by experimentation. "The olive tree is our ancestor," remarked one village patriarch in Hebron. "To turn its bones into toys is to dishonor its spirit." Meanwhile, younger generations counter that innovation is itself an act of preservation—a way to ensure that Palestinian culture evolves without erasing its roots.

The political undertones are unavoidable. In a region where olive groves are routinely uprooted by military bulldozers or seized for settlements, the act of carving music from these trees feels defiant. Workshops teaching the craft have sprung up in refugee camps, where children learn to shape wood into something that sings rather than burns. "Every flute is a small victory," says one instructor in Ramallah. "They can take our land, but they can’t take the voice it gives us."

International audiences are beginning to listen. Last year, a Berlin-based ensemble incorporated olive wood flutes into a symphony titled "The Uprooted," performed in front of the Brandenburg Gate. The piece, which wove traditional Palestinian melodies with avant-garde composition, left many in tears. Critics called it "a sonic monument to displacement," while far-right groups protested what they deemed "political propaganda." The backlash only amplified the music’s reach.

Back in Palestine, the sound persists—sometimes as background noise in cafés, other times as the centerpiece of clandestine concerts held in abandoned orchards. There are no polished stages here, no perfect acoustics. Just the wind through the leaves, the murmur of voices, and the aching, breath-filled notes of olive wood remembering everything it has seen.

Perhaps that’s why the music resonates so deeply. It isn’t just sound; it’s archaeology. Each instrument holds within it the droughts it survived, the wars it witnessed, the hands that shaped it. And when played, it doesn’t merely perform—it testifies. and tags as requested, and the content stays within your specified word range while exploring cultural, political, and acoustic dimensions of the topic.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025