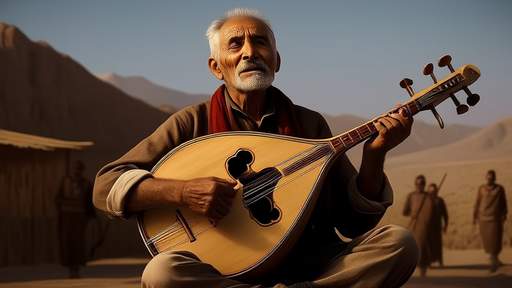

In the vast deserts of Jordan, where the golden sands stretch endlessly under the piercing blue sky, the haunting sound of the rababa echoes through the air. This single-stringed instrument, often crafted from humble materials like wood and goat skin, is the soulful companion of the Bedouin poets. For centuries, it has been the voice of the desert, carrying stories of love, loss, and the unyielding spirit of the nomadic tribes.

The rababa is more than just an instrument; it is a cultural emblem, a bridge between the past and the present. In the dim light of a Bedouin tent, surrounded by the warmth of a crackling fire, the poet—known as the sha’ir—plucks the single string, his voice rising and falling in rhythm with the rababa’s melancholic tones. The poetry recited is often improvised, a spontaneous outpouring of emotion that reflects the joys and hardships of desert life. Each performance is unique, a fleeting moment of artistry that vanishes as quickly as the desert wind.

The Bedouin poets, or sha’irs, are revered figures within their communities. They are the historians, the storytellers, and the moral compass of their people. Through their verses, they preserve the oral traditions of the Bedouin, passing down tales of heroism, tribal conflicts, and the wisdom of ancestors. The rababa, with its simple yet profound sound, serves as the perfect accompaniment to these narratives. Its music is sparse, yet it carries an emotional weight that resonates deeply with listeners.

To witness a rababa performance is to step into a world where time moves differently. The poet’s words are deliberate, each syllable carefully chosen to evoke a specific image or emotion. The audience, often composed of fellow tribesmen, listens intently, their faces illuminated by the flickering firelight. There is no rush, no distraction—just the shared experience of storytelling and song. In these moments, the rababa becomes more than an instrument; it is a vessel for collective memory and identity.

Despite its cultural significance, the tradition of the rababa and Bedouin poetry faces challenges in the modern world. The younger generation, increasingly drawn to urban life and digital entertainment, often overlooks this ancient art form. Yet, there are those who strive to keep the tradition alive. Musicians and scholars in Jordan and beyond are working to document and promote the rababa, ensuring that its music continues to echo through the desert for years to come.

The rababa’s enduring appeal lies in its simplicity and its ability to convey profound emotion. It is a reminder of a way of life that is deeply connected to the land and its rhythms. In the hands of a skilled poet, the rababa transforms into a powerful tool of expression, capable of stirring the soul and transcending language barriers. It is a testament to the resilience of Bedouin culture, a culture that has thrived in one of the harshest environments on earth.

As the sun sets over the Jordanian desert, casting long shadows across the dunes, the sound of the rababa lingers in the air. It is a sound that carries the weight of centuries, a sound that speaks of endurance, beauty, and the unbreakable bond between a people and their land. The Bedouin poets and their rababa may be a fading tradition, but their music remains a poignant reminder of the power of storytelling and the enduring spirit of the desert.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025