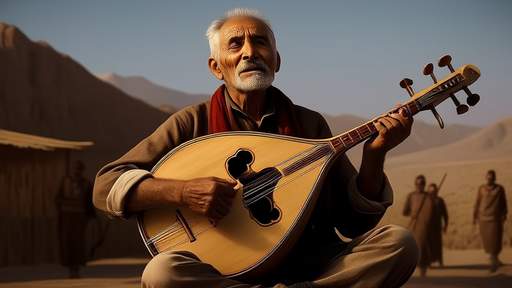

The haunting melodies of the Afghan rubab have echoed through the mountains and deserts of Central Asia for centuries. Carved from a single block of aged walnut wood, this double-chambered lute is more than an instrument—it is a living testament to the cultural exchanges that once flourished along the Silk Road. Its voice, at once resonant and melancholic, carries the weight of empires risen and fallen, of caravans that brought not only spices and silks but the very essence of human connection.

To hold a finely crafted rubab is to touch history. The best instruments are still made in Kabul’s old quarter, where luthiers trace their techniques to 16th-century Mughal workshops. The wood must be quarter-sawn from ancient walnut trees that once grew in the orchards of Herat, its tight grain ensuring both durability and acoustic warmth. "A rubab sings because it remembers the wind through those branches," explains Ustad Mahmoud, a master player whose calloused fingers have worn smooth the mother-of-pearl inlays of his father’s instrument. The goat skin stretched across its soundboard tightens in dry weather, requiring constant tuning—a metaphor, perhaps, for Afghanistan itself.

The instrument’s design reveals its journey. The three main strings of brass and gut mirror the Persian tar, while the sympathetic metal strings beneath show Indian sitar influence. Yet the rubab’s distinctive sound comes from its hollow neck, a feature unique to Central Asia that allows harmonics to shimmer like heat waves over the Dasht-e-Leili. When Marco Polo described hearing "lutes that weep" in Balkh, he likely encountered an ancestor of the modern rubab. Recent excavations near Mazar-i-Sharif uncovered terracotta figurines from the Kushan era (1st-3rd century CE) holding similar instruments, suggesting this sound may have accompanied Buddhist monks before Islam’s arrival.

Modern players bridge worlds. Homayun Sakhi, exiled in California, electrifies the rubab with effects pedals for jazz collaborations, while in Kabul, young women risk Taliban disapproval to study the instrument at underground music schools. The rubab’s pentatonic scales adapt eerily well to blues progressions, a fact noted by the late Abdul Wahid Nazeri during his collaborations with Western musicians. "The desert and the delta speak the same language of longing," he once remarked during a London performance that reduced the audience to stunned silence.

Conservationists now sound alarms. Decades of war have devastated Afghanistan’s walnut forests, with less than 12% of old-growth stands remaining. The last master carver of Herati-style rubabs, Abdul Samad, was killed in a 2021 rocket attack, taking irreplaceable knowledge with him. NGOs scramble to document tuning systems and playing techniques before they vanish, but as ethnomusicologist Sarah Morgan notes: "You can archive recordings, but not the way a master’s wrist turns when teaching a student to make the mountains weep."

Perhaps the rubab’s greatest lesson lies in its construction. The soundboard must be thin enough to vibrate freely yet thick enough to withstand the tension of strings. Like the cultures that birthed it, the instrument exists in this delicate balance—between strength and fragility, between memory and innovation. As Taliban edicts again threaten musical expression, the rubab’s persistence whispers that beauty, once woven into the grain of human experience, cannot be entirely silenced.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025