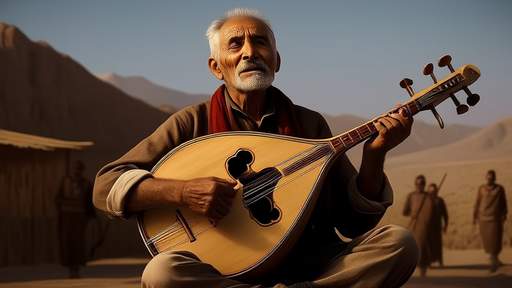

The haunting melodies of the mijwiz, a traditional Phoenician double-pipe reed instrument, have echoed through the Levant for millennia. Today, this ancient musical voice is experiencing a vibrant revival, reimagined by a new generation of Lebanese musicians who blend its primal tones with contemporary sounds. From the cedar-lined mountains of Lebanon to the bustling streets of Beirut, the mijwiz is undergoing a remarkable metamorphosis that honors its Phoenician roots while catapulting it into 21st-century soundscapes.

Carved from cane or bamboo and bound together with waxed thread, the mijwiz's distinctive parallel pipes produce a mesmerizing, slightly dissonant harmony that immediately transports listeners across time. What makes this instrument extraordinary is its circular breathing technique - players maintain an uninterrupted stream of sound by storing air in their cheeks while inhaling through their nose. This demanding skill, perfected by Bedouin and village musicians for centuries, creates the mijwiz's characteristic continuous wail that once carried across Phoenician trade routes and Mediterranean vineyards.

In Beirut's alternative music scene, experimental musicians are pushing the mijwiz beyond its traditional wedding and folk dance repertoire. Wissam Joubran, a virtuoso who trained under Syrian master musicians, has been pioneering electrified mijwiz performances. By running the ancient pipes through distortion pedals and loop stations, he creates layered soundscapes that wouldn't sound out of place in a Berlin techno club. "The mijwiz speaks in the voice of our ancestors," Joubran explains between sets at a dimly lit Beirut venue, "but it has something urgent to say about who we are today."

The instrument's revival isn't limited to avant-garde circles. Lebanese pop sensation Myriam Fares incorporated mijwiz riffs into her 2022 hit "Habibi Come to Dubai," creating an unexpected fusion that topped regional charts. This commercial success has sparked renewed interest among Lebanese youth, with music shops reporting a 300% increase in mijwiz sales over the past two years. At the prestigious Lebanese National Conservatory, enrollment for traditional wind instruments has doubled since 2020, with many students specifically requesting mijwiz instruction.

What makes the modern mijwiz movement particularly fascinating is its technological innovation. Lebanese instrument maker Karim Abou Zaki has developed a polycarbonate version of the traditional cane pipes. "The synthetic material maintains the authentic timbre while surviving Beirut's humidity," Zaki explains in his workshop, surrounded by both ancient and futuristic-looking prototypes. His designs include MIDI-compatible electronic mijwiz controllers that can trigger synthesizers while preserving the instrument's distinctive playing technique.

The global music community is taking notice. Last year, the mijwiz featured prominently in the score of the video game "Assassin's Creed: Phoenician Winds," exposing millions of players worldwide to its haunting sound. Ethnomusicologists from Oxford to Tokyo have begun studying this resurgence, with several doctoral dissertations in progress examining how the instrument bridges ancient Phoenician culture with contemporary Lebanese identity. The Smithsonian Institution recently acquired a collection of traditional and modified mijwiz instruments for their permanent collection.

Yet for all its modern adaptations, the soul of the mijwiz remains rooted in village traditions. In Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, 78-year-old Youssef al-Hadad still crafts mijwiz pipes using methods passed down through generations. "The cane must be cut at dawn when the sap is sweetest," he murmurs, running gnarled fingers along fresh-cut reeds. His apprentices include both local shepherds and musicology students from the American University of Beirut - a testament to the instrument's enduring appeal across generations and social boundaries.

As Lebanon navigates complex political and economic challenges, the mijwiz has emerged as an unlikely cultural unifier. During the 2019 protests, demonstrators across sectarian divides found common ground in mijwiz-led chants. The instrument's primal, wordless voice seemed to articulate collective hopes and frustrations that transcended language barriers. This social dimension adds profound resonance to the musical revival, suggesting the ancient pipes still fulfill their original purpose as instruments of community expression.

The future of the mijwiz appears bright as it continues evolving. Lebanese-Dutch composer Rabih Bahlawan recently premiered a mijwiz concerto with the Rotterdam Philharmonic, blending the instrument with full orchestral arrangements. Meanwhile, in Beirut's underground clubs, DJs are sampling mijwiz loops into electronic dance tracks. This spectrum of interpretations - from classical to club - demonstrates the instrument's remarkable versatility and enduring relevance.

From Phoenician temples to European concert halls, from Bedouin campfires to Beirut nightclubs, the mijwiz continues its extraordinary journey. Its modern reincarnations honor three thousand years of musical heritage while fearlessly exploring new creative frontiers. As one young musician at a Beirut open mic night remarked while packing up his carbon-fiber mijwiz: "This isn't just history - it's the future sounding through bamboo." The double-piped voice of ancient Phoenicia, it seems, still has much to say to the modern world.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025