The ancient land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, often referred to as Mesopotamia, holds within its soil the echoes of humanity's earliest musical traditions. Among the most fascinating discoveries are the Santur-like instruments and the musical notations encoded in cuneiform script, revealing a sophisticated understanding of sound and rhythm that flourished over 4,000 years ago. These artifacts, scattered across modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, whisper secrets of a civilization that revered music as both an art and a science.

Recent excavations near the ruins of Ur and Nineveh have unearthed clay tablets inscribed with what scholars now recognize as the world's oldest known musical notations. These markings, pressed into wet clay with a reed stylus, depict intricate harmonic scales and rhythmic patterns that would not be out of place in contemporary Iraqi maqam traditions. The connection between these ancient notations and the modern Santur (a trapezoidal hammered dulcimer) becomes particularly striking when examining the interval structures - the same fourths and fifths that define Middle Eastern music today.

What makes these discoveries revolutionary is their demonstration of a codified musical language existing nearly two millennia before the Greek modes that would later influence Western music. The cuneiform tablets don't merely list notes; they provide instructions for performance, including indications for tuning and even emotional expression. One particularly well-preserved tablet from the Old Babylonian period (about 1900-1600 BCE) contains what appears to be a drinking song, complete with lyrics and melodic directions - the Bronze Age equivalent of sheet music.

The musical system revealed by these tablets operates on a heptatonic scale remarkably similar to those still used in traditional Iraqi music. This continuity suggests an unbroken (though evolving) musical tradition stretching from the Sumerian courts to the modern Santur players of Baghdad. Archaeomusicologists have managed to reconstruct several of these ancient compositions, and when played on replica instruments based on excavated finds, the melodies resonate with what our modern ears would immediately identify as distinctly Middle Eastern tonalities.

Perhaps most astonishing is the mathematical precision evident in these early musical notations. The Mesopotamians appear to have developed a Pythagorean tuning system long before Pythagoras himself, using ratios to determine pitch relationships. This mathematical approach to music reflects the broader Mesopotamian worldview where art, science, and religion intertwined seamlessly. The same scribes who calculated astronomical events and developed advanced irrigation systems also codified the rules of musical composition.

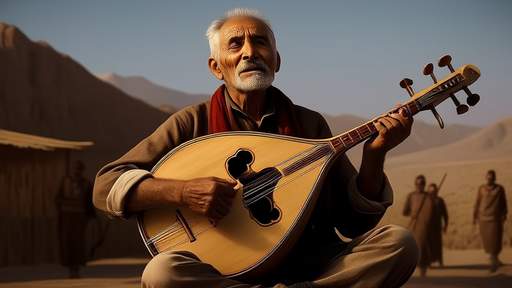

The modern Santur, with its precisely arranged bridges and carefully tuned strings, carries forward this ancient legacy of mathematical music-making. When a contemporary Iraqi musician strikes the Santur's strings with their delicate mallets, they are unwittingly recreating sonic relationships first discovered by musicians who played for the courts of Hammurabi and Sargon. The instrument's distinctive trapezoidal shape, interestingly, bears resemblance to depictions of ancient Mesopotamian zithers found on cylinder seals and temple reliefs.

As research continues, scholars are beginning to understand how these musical traditions may have spread. The Assyrian empire's vast trade networks likely carried Mesopotamian musical ideas across the ancient world, influencing the development of instruments and scales from Egypt to India. This diffusion might explain why the Santur and its variants appear across such a wide geographical area today, from the Persian Santoor to the Indian Santoor and beyond.

The study of Mesopotamian music also challenges Western-centric narratives of musical evolution. While European music history often begins with ancient Greece, the cuneiform tablets prove that advanced musical theory existed in Mesopotamia centuries earlier. This realization is prompting a reevaluation of how musical ideas developed and spread in the ancient world, with Mesopotamia emerging as a crucial wellspring of musical innovation.

For modern musicians, these ancient notations offer both inspiration and practical lessons. Several contemporary ensembles have begun incorporating reconstructed Mesopotamian melodies into their performances, creating a dialogue across millennia. The Santur, as a living descendant of this tradition, serves as the perfect medium for such temporal bridging - its metallic strings vibrating with notes that would have been familiar to scribes in ancient Babylon.

As archaeologists continue to decipher more cuneiform tablets, who knows what other musical secrets might emerge from the dust of Iraq's ancient cities? Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of humanity's musical origins, reminding us that the songs we consider traditional today are but the latest iterations of an artistic conversation that began when the first Mesopotamian musician plucked a string or struck a drum in worship, celebration, or simple human expression.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025