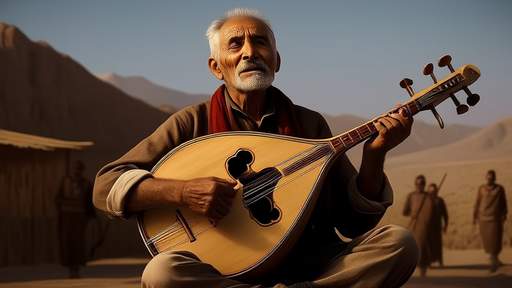

The air in Tehran’s historic Vahdat Hall hummed with anticipation as the annual Persian poetry competition reached its crescendo. Among the poets, whose verses wove intricate tapestries of love, loss, and longing, stood an often-overlooked yet indispensable figure: the tar player. This lute-like instrument, with its melancholic timbre, has been the silent companion of Persian poetry for centuries, and on this night, its strings breathed life into words that had yet to be spoken.

The role of the tar in Persian poetry competitions is both subtle and profound. Unlike a mere backdrop, the instrument engages in a delicate dance with the poet, responding to the cadence of their voice, the weight of their pauses, the sudden crescendos of emotion. It is not an accompaniment but a conversation—one where the tar anticipates, challenges, and sometimes even contradicts the poet’s words. The best tar players, those who have spent decades mastering the radif (the traditional Persian musical system), understand that their art lies in the spaces between the verses, in the unspoken resonance that lingers after a line is delivered.

Mohammad Reza Lotfi, a revered tar virtuoso, once described the relationship between poet and musician as a "marriage of shadows." "The poet casts the light," he said, "and the tar player follows with the shade." This interplay was evident in the performances at Vahdat Hall, where young poets, some reciting for the first time, found their words amplified by the tar’s mournful cry. The instrument’s ability to mirror the emotional undercurrent of the poetry—whether the sharp sting of betrayal or the slow ache of nostalgia—transformed each recitation into a multisensory experience.

Yet, the tar player’s artistry extends beyond mere emotional mimicry. In the hands of a master, the instrument becomes a co-creator, shaping the audience’s interpretation of the poem. A sudden shift from the shur mode to mahur can turn a lament into a celebration; a fleeting tremolo might hint at irony beneath seemingly sincere words. This linguistic-musical synergy is uniquely Persian, rooted in a tradition where poetry and music were once inseparable. Even as modern competitions formalize the structure of these events, the tar remains a bridge to that older, more fluid artistry.

Behind the scenes, the preparation for these performances is as rigorous as it is intuitive. Tar players spend hours with the poets, not just rehearsing lines but discussing the subtext of each verse—the historical allusions, the personal wounds, the unspoken rebellions. "You cannot play for Rumi the way you play for Hafez," explained Parisa Khosravi, one of the few female tar players to gain prominence in this male-dominated space. "Rumi’s words spiral upward; they demand open strings and wide intervals. Hafez is a labyrinth—you must pluck each note with precision, like solving a riddle."

The audience, too, plays a role in this tripartite exchange between poet, musician, and listener. In Iran, where poetry is not just art but cultural memory, the crowd’s reactions—a collective intake of breath, a murmur of recognition at a well-placed musical phrase—feed back into the performance. When the tar player subtly quotes a melody from a classic ghazal mid-recitation, the room erupts in knowing applause. These moments reveal the deep literacy of Persian listeners, who hear not just the words and music of the present but the echoes of centuries.

As the competition drew to a close, the winning poet bowed not just to the judges but to the tar player beside him—a gesture that spoke volumes. In an age of digital distractions and fragmented attention, the Persian poetry competition, with its living tradition of spontaneous musical dialogue, offers something rare: a reminder that art is not made in isolation. The tar’s strings, like the threads of Iran’s poetic heritage, bind past to present, voice to instrument, solitary creation to collective witness. And in that binding, something transcendent emerges—not just poetry, not just music, but the ineffable third thing that exists only in their confluence.

The next morning, in a small café near Tehran University, the tar player from the competition sat with his instrument case beside him. When asked about the previous night’s performance, he smiled and plucked a single string. The note hung in the air, unresolved. "That," he said, "was the answer to a question the poet didn’t know he was asking."

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025