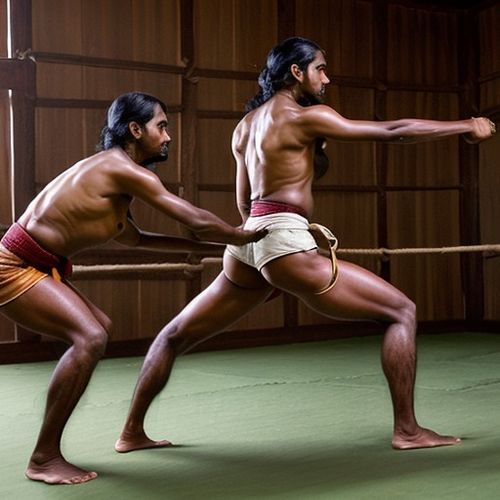

In the heart of Southeast Asia, where ancient traditions collide with modern combat sports, Myanmar Lethwei stands as one of the world's most brutal and fascinating martial arts. Unlike its more widely known cousin, Muay Thai, Lethwei permits fighters to use not just fists, elbows, knees, and shins—but also bare-knuckle headbutts, making it a uniquely visceral spectacle. Rooted in Myanmar's warrior culture, this full-contact discipline has evolved from battlefield techniques into a celebrated national sport, captivating both local enthusiasts and international audiences.

The origins of Lethwei trace back over a thousand years to the Pyu and Mon civilizations, where it was developed as a form of military training. Historical records from the Bagan era (9th to 13th centuries) depict warriors engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat resembling modern Lethwei. Unlike other Southeast Asian martial arts, which absorbed influences from Indian or Chinese traditions, Lethwei remained distinctly Burmese—a raw, unfiltered expression of close-quarters combat. For centuries, matches were held during festivals, with fighters wrapping their hands in hemp ropes to protect their knuckles while increasing the damage inflicted on opponents.

What truly sets Lethwei apart is its rule structure—or lack thereof. Traditional matches had no time limits, continuing until one fighter could no longer continue. Even today, knockouts are the most decisive way to win, though draws are common if both fighters remain standing after five rounds. The most controversial aspect—the allowance of headbutts—makes it arguably the most dangerous sanctioned striking sport in existence. Fighters don't wear gloves, only hand wraps, amplifying the impact of every blow. This brutal authenticity has earned Lethwei nicknames like "The Art of Nine Limbs" (counting the head as a weapon) and "The World's Most Dangerous Martial Art."

Modern Lethwei has undergone significant changes while preserving its essence. Since the 1990s, international exposure has led to rule modifications for safety, including timed rounds and weight classes. Organizations like the World Lethwei Championship (WLC) have professionalized the sport, hosting events in Yangon's Thuwunna Stadium that draw thousands. Yet traditional elements persist: fighters still perform the Let Khama (war dance) before matches, and rural villages host bareknuckle bouts on earthen pits. The sport's growing popularity has sparked debates about commercialization versus cultural preservation, with purists arguing that sanitizing Lethwei risks diluting its identity.

Training regimens for Lethwei fighters border on masochistic. Beyond standard striking drills, practitioners condition their bodies by kicking banana trees, striking sand-filled sacks, and performing hundreds of repetitions with weighted ankle wraps. The most feared technique—the spinning elbow—requires years to master without telegraphing the movement. Nutrition remains traditional as well; fighters consume htamin jin (fermented rice) for energy and apply thanaka (a natural paste) to prevent cuts. This combination of ancient wisdom and modern training methods produces athletes capable of absorbing tremendous punishment while delivering fight-ending strikes.

Internationally, Lethwei faces both fascination and resistance. While countries like Japan and Russia have embraced exhibitions, regulatory bodies in Western nations balk at legalizing a sport permitting headbutts. Yet the global MMA community increasingly studies Lethwei's techniques, particularly its clinch work and unorthodox angles of attack. Fighters like Dave Leduc, the first foreigner to win a Lethwei world title, have become ambassadors, arguing that with proper oversight, the sport could follow Muay Thai's path to worldwide acceptance. Streaming platforms now broadcast major events, exposing new audiences to what many consider striking arts' final frontier.

The future of Lethwei hangs in a delicate balance between tradition and progress. As Myanmar emerges from political isolation, its signature martial art stands at a crossroads—preserve its blood-and-earth authenticity or adapt for Olympic recognition? Younger generations of fighters increasingly favor protective gear, while veterans warn against losing the sport's soul. What remains undeniable is Lethwei's raw power to captivate; in an age of sanitized combat sports, it offers something increasingly rare—uncompromising violence steeped in cultural heritage, where every fight tells a story older than the nation itself.

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/May 8, 2025

By William Miller/May 8, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/May 8, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/May 8, 2025

By Jessica Lee/May 8, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/May 8, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 8, 2025

By Christopher Harris/May 8, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/May 8, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/May 8, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Noah Bell/May 8, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 8, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 8, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/May 8, 2025

By Eric Ward/May 8, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/May 8, 2025

By Daniel Scott/May 8, 2025

By Eric Ward/May 8, 2025